In the second of this series I describe a case of Acanthaemoeba keratitis (AK) that was misdiagnosed for a prolonged period which resulted in a devastating outcome. This is one of half a dozen similar medico-legal cases I have dealt with in recent times all with a similar story.

Case history

A monthly soft contact lens wearer presented to eye casualty with a red eye. She had been seen a week previously by her general practitioner and had been prescribed chloramphenicol ointment. Her symptoms had failed to improve. She had discontinued contact lens wear on the advice of her GP.

Examination showed ciliary injection with punctate corneal staining. Visual acuity at the time was 6/12 improving to 6/9.

A diagnosis superficial punctate keratitis secondary to contact lens wear was made and Ciloxan prescribed.

Two weeks later the condition had worsened and the patient was in significant pain. Examination at that time showed an epithelial defect which was dendritiform in nature. A diagnosis of herpes simplex keratitis (HSK) was made and antiviral treatment commenced in association with steroid drops. The clinical course fluctuated between improvement and then deterioration for eight weeks.

Eventually the patient was referred to a corneal service. The visual acuity in the affected eye had deteriorated to hand motions only, while examination showed a very large epithelial defect with an underlying ring infiltrate. A working diagnosis of AK was established. Cultures for acanthamoeba were negative, but confocal microscopy showed the presence of numerous cysts in the corneal stroma. Treatment with hourly PHMB was initiated. Despite this the corneal opacity persisted and the pain became intractable. Eventually evisceration was carried out.

Discussion

This patient’s visual loss could have been easily prevented. The history is typical. A patient presents to primary care with a red eye, is treated with antibiotics which fails to resolve the problem. Corneal changes ensue which are misdiagnosed as HSK. Various antiviral and steroid treatments are continued for a period of weeks or months. Only then is AK considered.

Early diagnosis is crucial. Failure to consider AK as a diagnosis in a contact lens wearer with corneal pathology that fails to resolve or seems to be a HSK can be considered negligent. It is often the consultant who has to bear the burden of this negligence even though it was one of his or her team who made the misdiagnosis. Furthermore, once the diagnosis of HSK is made, it tends to propagate throughout the clinical notes and it is not challenged by successive doctors. It is our responsibility to educate and inform juniors and middle grades to suspect AK in any contact lens wearer with a supposed diagnosis of HSK.

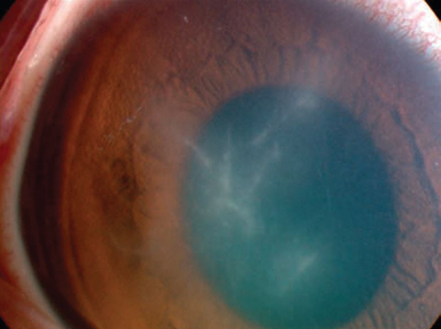

Figure 1: Radial keratoneuritis secondary to Acanthamoeba keratitis.

A study in the USA [1] reviewed a large number of cases finding that the median time to diagnosis from onset of symptoms was 27 days. In a significant proportion of these patients the misdiagnosis of HSK was made. Outcome in a third was worse than 6/60.

Another large study in Australia [2] showed a mean time of 44.1 +/- 34.0 days between initial presentation and diagnosis. Of those with a diagnostic delay of more than one month, 57% had been mistakenly diagnosed with HSK. A German study [3] reported a mean interval between first symptoms and correct diagnosis of 42 days. A further paper [4] found that herpes simplex keratitis was the misdiagnosis in 70%.

ALWAYS consider AK in the event of failure to respond to first-line therapy for bacteriaI or presumed HSV-related keratitis in a contact lens wearer. Studies have shown that if effective treatment is delayed for three weeks or more the final outcome is worse [5].

Diagnostic studies such as confocal microscopy can miss AK. A high index of suspicion should be maintained even in the presence of negative findings. Bacterial infection may be co-existent so a positive culture does not exclude AK.

Educating patients is vital to ensure proper hygiene when using contact lenses. Topping up contact lens solutions or reusing daily contact lenses are practices fraught with risk. More silicon hydrogel extended wear contact lenses are being used, potentially explaining the increasing incidence of AK.

As in this case and many others the patients were prescribed steroids. The use of steroids prior to a diagnosis of AK has been shown to have a negative impact on final outcome [6].

We have a duty of care to detect AK earlier and we should educate all members of our team that unresponsive HSK in a contact lens wearer should be suspected to be AK until proven otherwise.

AK is a visually devastating condition which can and should be picked up earlier. It is getting more common and yet our index of suspicion seems to have remained disappointingly low.

References

1. Ross J, Roy SL, Mathers WD, et al. Clinical characteristics of Acanthamoeba keratitis infections in 28 states, 2008 to 2011. Cornea 2014;33(2):161-8.

2. Butler TK, Males JJ, Robinson LP, et al. Six-year review of Acanthamoeba keratitis in New South Wales, Australia: 1997-2002. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2005;33(1):41-6.

3. Bernauer W, Duguid GI, Dart JK. Early clinical diagnosis of acanthamoeba keratitis. A study of 70 eyes. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 1996;208(5):282-4.

4. Thebpatiphat N, Hammersmith KM, Rocha FN, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a parasite on the rise. Cornea 2007;26(6):701-6.

5. Bacon AS, Dart JK, Ficker LA, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis. The value of early diagnosis. Ophthalmology 1993;100:1238-43.

6. Carnt N, Robaei D, Watson SL, et al. The impact of topical corticosteroids used in conjunction with antiamoebic therapy on the outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology 2016;123(5):984-90.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME