Ophthalmologists in the UK are relatively infrequently faced with a patient requesting surgery for a pterygium. This condition is more common where ultraviolet exposure is greater, especially if coupled with activities associated with ocular surface irritation. For this reason, a pterygium is also known as ‘surfer’s eye’, since surfers in warmer climates are exposed to increased ultraviolet radiation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Occasionally UK surfers get to risk surfer’s eye and enjoy

warmer climate waves such as in Arrifana, South West Portugal.

The case report this month relates to an unusual late complication for treatment of a pterygium. An 83-year-old man presented with a two-month foreign body sensation in his right eye. His past ophthalmic history included an excision of a pterygium, combined with radiotherapy in 1995. He had type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was well controlled, and had no other medical history. There was no history of ocular trauma.

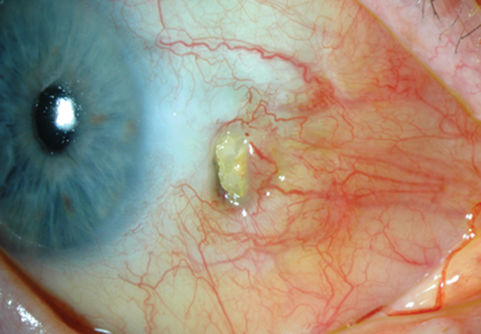

His acuity was 6/9 bilaterally. There was an unusual appearance of the nasal sclera at the site of previous pterygium excision and beta irradiation (Figures 2 and 3). This lesion was 6mm x 4mm in size, and examination under topical anaesthesia at the slit-lamp found the lesion to have a hardened consistency and intimately related to the sclera. The conjunctiva, except for its anterior protruding portion, enveloped the lesion. The conjunctival vessels were locally injected. The adjacent sclera had thinned, and there was an adjacent dellen.

Figure 2: Unusual appearance of the nasal sclera at the site of previous pterygium excision

and beta irradiation. The lesion had a hard consistency and was intimately related to the sclera.

Figure 3: Close-up of the abnormal scleral lesion at the site of previous pterygium excision and beta irradiation.

Following a trial of ocular lubrication, the patient’s symptoms were relieved and the dellen resolved. He was offered a biopsy, but given that his symptoms had settled he understandably was not keen for any surgical intervention. Six months later findings remain stable.

Pterygium is a pathology of the ocular surface characterised by proliferation, inflammation and fibrovascular change. It can cause irritation, blurred vision (astigmatism) and even diplopia if eye movement is restricted.

Simple excision of a pterygium is associated with a high rate of recurrence. Today, excision of a pterygium is typically combined with a conjunctival autograft or amniotic membrane transplant (sometimes combined with anti-metabolites) to significantly reduce the risk of recurrence. Historically, simple excision was combined with beta irradiation, which was successful in reducing the rate of recurrence (0.5% [1] to 16% [2]), but unfortunately was associated with a relatively high late complication profile.

Tarr and Constable investigated the late complications of beta irradiation in 63 eyes of 57 Australian patients (average follow-up 12 years) [2]. Scleral thinning / ulceration occurred in 51 eyes, and four of these subsequently suffered pseudomonas endophthalmitis. Radiation induced cataract occurred in three eyes. Ptosis, symblepharon and iris atrophy were also seen. The guidance from this paper highlighted that beta irradiation can be a significant cause of iatrogenic disease, and that modifications to the radiation technique were suggested. Fortunately, the success of pterygium excision with conjunctival autograft has reduced the need for such radiotherapy.

This patient’s story is interesting, since it would appear that he has developed an abnormal focus of sclera, 15 years after his radiotherapy. This area perhaps reflects dystrophic calcification. Metaplastic transformation to osteoblasts is another possibility. Dysplasia (carcinoma-in-situ / conjunctival intra-epithelial neoplasia) is a relevant concern and cannot be excluded. However, the lack of progressive change is reassuring and makes this diagnosis less likely.

It would be useful to biopsy this lesion to help obtain a tissue diagnosis but for reasons explained above the patient was not keen for this. Dystrophic calcification of the sclera following previous irradiation at the time of pterygium excision is not well described in the literature, so these comments remain speculative without a biopsy or evidence base.

Reassuringly, findings have remained stable with minimal symptoms… so UK surfers should perhaps continue to enjoy their pilgrimages to warmer climates!

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the patient for allowing the publication of their story, as well as Mr Steve Slater (Medical Photographer, Plymouth Royal Eye Infirmary), Mr Tim Freegard (Consultant Ophthalmologist, Plymouth Royal Eye Infirmary) and Mr Vasant Raman (Consultant Ophthalmologist, Plymouth Royal Eye Infirmary) for helping with this case report.

References

1. Ozarda AT. Evaluation of post-excisional strontium-90 beta ray therapy for pterygium. South African Medical Journal 1977;70:1304.

2. Tarr KH, Constable J. Late complications of pterygium treatment. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1980;64:496-505.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME