A worrying cause of headache is raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Papilloedema is a vital clue for accurate diagnosis and performing fundoscopy is essential in detecting this sign. The authors review the use of fundoscopy in their own district general hospital.

Neurological emergencies, of which headaches account for a significant proportion, are the third leading trigger of acute medical presentations and represent up to 25% of the medical take; this is second only to cardiac and respiratory cases [1]. The likelihood of headache sufferers seeking help is low, and when they do, the condition is less than optimally managed [2].

The British Association for the Study of Headache (BASH) National Headache Management System for Adults 2019 guidelines recommend a thorough neurological investigation including fundoscopy when assessing a patient with headache [3]. Additionally, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) also advises carrying out fundoscopy as part of a neurological examination for headache, as well as cranial and peripheral nerve examination [4].

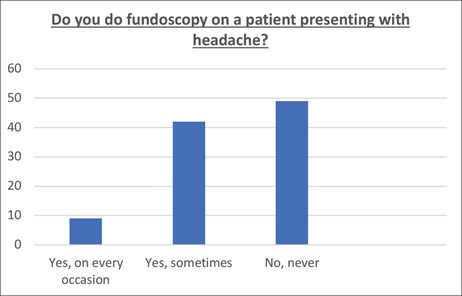

Figure 1: Numbers of respondents who perform fundoscopy on a patient presenting with headache.

Figure 2: Pie chart showing whether respondents were aware of the BASH guidelines.

Why is this important?

A worrying cause of headache is raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Papilloedema is optic disc swelling specifically secondary to raised ICP and is a vital clue for accurate diagnosis; performing fundoscopy is essential in detecting this sign [5]. However, studies have revealed that a minority of doctors would perform fundoscopy in such cases [1]. We have therefore sought to assess the compliance of our acute medical department with BASH guidelines, and to bring to light the impediments to delivering appropriate management in patients presenting with headache and suggest improvements.

Results

A total of 59 acute medical clerkings with a presentation of headache to our district general hospital between August and October 2017 were reviewed, 38/59 (64%) of whom were female and 21/59 (36%) male. Patients’ age ranged from 18 to over 70 years; the most numerous age group consisted of patients 70+ years old (27%). The majority (71%) of clerkings were carried out by junior and senior house officers.

“Fundoscopy plays a crucial role in uncovering a diagnosis of raised ICP. Papilloedema is the clue”

Fundoscopy was performed in the initial acute medical clerking of 7/59 (12%) patients, only one of whom had documentation that their pupils were dilated beforehand. Of the remaining 52/59 (88%) patients who did not have fundoscopy performed, none had it done on the subsequent post take ward round.Furthermore, a survey was emailed to all doctors within the Trust to gather information on their level of awareness of BASH guidelines, whether they perform fundoscopy in patients presenting with headache, what they believed were obstacles and what interventions they felt would help to increase the likelihood of them doing so. Thirty-three responses to the survey were received. Nine percent of respondents declared they always perform fundoscopy, 42% sometimes and 49% never. Seventy percent of respondents were not aware of the BASH guidelines.

The most frequent reasons given for not performing fundoscopy were: lack of ophthalmoscopes and dilating eyedrops (and / or lack of awareness of their location), insufficient knowledge on fundoscopy technique, and low confidence when interpreting findings. Respondents ranked readily available ophthalmoscopes as the most likely intervention to encourage them to perform fundoscopy, followed by further knowledge on fundoscopy technique and interpretation of findings. Suggestions to encourage carrying out fundoscopy included making it a part of the clerking proforma and the delivery of teaching sessions.

Discussion

Headache is a common symptom associated with many conditions and accounts for up to 5% of attendances to emergency departments and acute medical units [6]. Headaches are classified as either primary or secondary. Primary headaches, such as migraine, are usually benign. Secondary headaches are a symptom of another disorder [6]. The majority of patients presenting with headache have primary headaches, with migraine being the most frequent diagnosis [7]. However, management of headache in the acute setting should focus on excluding serious secondary causes, of which raised ICP is one [6].

The combination of headache, papilloedema and vomiting is considered indicative of raised ICP; the headache is oftentimes worse on waking, straining and bending [8]. Prompt diagnosis of raised ICP is important as it has several serious causes including neoplasms, haematoma, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid haemorrhage, encephalitis and idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) [8]. In addition to a comprehensive headache history and examination (which includes assessment of vital signs, mental state, extracranial structures, signs of meningism, and general neurological examination), fundoscopy plays a crucial role in uncovering a diagnosis of raised ICP [4]. Papilloedema is the clue.

Suspected papilloedema must be urgently confirmed or refuted by specialist ophthalmic examination [5]. If confirmed, it is essential to exclude intracranial causes of raised ICP through appropriate and timely brain imaging; in fact, patients with papilloedema should be considered to have an intracranial mass until proven otherwise [5,9]. This is done through urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) of the head [9]. CT or MRI venography should also be performed within 24 hours to exclude a cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [9]. If brain imaging is normal, the next step is to assess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure by lumbar puncture manometry where a raised CSF opening pressure would be indicative of IIH [9].

Though both BASH and NICE guidelines advise fundoscopy as an essential component of initial medical examination of such patients, our results show that this is not commonplace practice. Alarmingly, we discovered that most doctors were unaware of the guidelines in the first instance.

Interestingly, Binks et al. found that most doctors felt confident in managing certain life-threatening conditions, whereas only a minority would feel comfortable performing fundoscopy [1]. In their study, responses suggested difficulty in accessing equipment, as well as lack of technical ability plays a role in this [1]. In fact, it was found that junior doctors’ headache knowledge was deemed poorer than almost any other acute medical presentation and that confidence gaps existed even at senior level [1].

Such findings are not dissimilar to our study where it was also found that a lack of equipment (or lack of knowledge of their location) as well as poor technical skills and confidence in interpretation of findings contributed to a lack of fundoscopy. Similar to Binks et al. we found that increased medical education on this topic is needed, including medical school, junior doctor and other postgraduate teaching [1]. Furthermore, an adequate supply of equipment and knowledge of its location is essential, which can be achieved through appropriate signposting and the dissemination of Trust-wide informative emails.

References

1. Binks S, Nagy A, Ganesalingam J, Ratnarajah A. The assessment of headaches on the acute medical unit: is it adequate and how could it be improved? Clinical Medicine 2017;17(2):114-20.

2. Kernick D. Assessment and diagnosis of headache. Practice Nursing 2011;22(3):114-8.

3. BASH. National Headache Management System for Adults 2019:

https://www.bash.org.uk/downloads/

guidelines2019/01_BASHNationalHeadache

_Management_SystemforAdults_2019

_guideline_versi.pdf

4. NICE. Scenario: Headache – diagnosis. 2019:

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/

headache-assessment/diagnosis/

headache-diagnosis/

5. Lowth M. Optic Disc Swelling including Papilloedema. Patient January 2016:

https://patient.info/doctor/optic-disc

-swelling-including-papilloedema

6. Chinthapalli K, Logan AM, Raj R, Nirmalananthan N. Assessment of acute headache in adults – what the general physician needs to know. Clinical Medicine 2018;18(5):422-7.

7. Doretti A, Shestaritc I, Ungaro D, et al. Headaches in the emergency department –a survey of patients’ characteristics, facts and needs. Journal of Headache & Pain 2019;20(1):1-6.

8. Henderson R. Raised Intracranial Pressure. Patient August 2015:

https://patient.info/doctor/

raised-intracranial-pressure

9. Wakerley BR, Mollan SP, Sinclair AJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: update on diagnosis and management. Clinical Medicine 2020;20(4):384-8.

(All links last accessed August 2021)

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Secondary causes of headache are due to another disorder, which may be serious, and it is therefore essential to rule these out.

-

The need for raising awareness about guidelines for headache management which include fundoscopy.

-

Papilloedema is a key sign of raised ICP; fundoscopy is necessary for identifying this.

-

A greater amount of teaching on fundoscopy technique and interpretation of ophthalmology signs is required to increase confidence in non-ophthalmology doctors.

-

Adequate equipment and knowledge of their location is required in the non-ophthalmology setting.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank Katja Christodoulou, Gastroenterology Registrar, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital and Timothy Chapman, Consultant, Respiratory Medicine, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital for their work on the audit on which this article is based

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME